Like many mental health issues, depression is often regarded as a non-illness; this could not be further from the truth. Depression is an illness. Unlike some other illnesses, such as diabetes or Meniere’s Disease, depression affects the whole body, feeds off other illnesses, and affects and infects other people around. Although not genetic, depression is still capable of being passed down the generations. Depression has been called the black dog, I am not sure this is right; it is so insidious and harmful it is more like the mind’s version of a bacterial infection.

Before I go any further, as is often the case with statistics, it is challenging to get like-for-like data, but I have drawn together some of the latest data on depression.

Some figures to think about

Just some of the latest statistics show the prevalence of depression during this cost of living crisis (data taken from the ONS survey conducted between 29/09/2022 and 23/10/2022):

- 1 in 6 people are struggling with moderate to severe depression – 10% higher than pre-pandemic levels

- Depression rates are higher among:

- the long-term sick who cannot work (59%)

- unpaid carers who are working 35+ hours a week (37%)

- disabled adults (35%)

- people living in deprived areas (25%)

- young adults (28%)

- single-person households (21%)

- women (19%) – just for balance – men (14%) – but this figure is likely to be underreported because men are ‘shy’ at seeking help or admitting problems

- 1 in 4 of the respondents, struggling to pay their energy bills, reported moderate to severe depression.

- 1 in 3 of those struggling with moderate to severe depression had to borrow more; compare this to the 1 in 6 who have either no or mild symptoms of depression.

- 145,000 people accessed the NHS Talking Therapies programme in the year up to August 2022, up 5% on the year before.

The example of unpaid carers.

All these figures are likely to be related. For example, if we look at the issue of unpaid carers, we can find several strands coming together.

Let’s go from the top. The latest census reported that 5.7 million people in the UK provided unpaid care, about 10% of the population, half of whom provided more than 20 hours of care a week. Carers (UK) research doubled the number of unpaid carers to about 10.9 million!

Drawing on research by Petrillo and Bennett (2022) p.20, there are about 3.7m unpaid carers in the UK, and, in England, while the majority are women (1.9m), the number of men providing unpaid care is not far behind, despite media portrayals (1.7m).

The suggested breakdowns between women and men across the UK are:

- In England – 1.9m women and 1.7m men

- In Wales: 110,000 women and 100,000 men

- In Scotland: 190,000 women and 150,000 men

- In Northern Ireland: 67,000 women and 58,000 men

To me, differentiating between men and women is a red herring, which is ultimately divisive.

Inexperienced, unqualified, unprepared

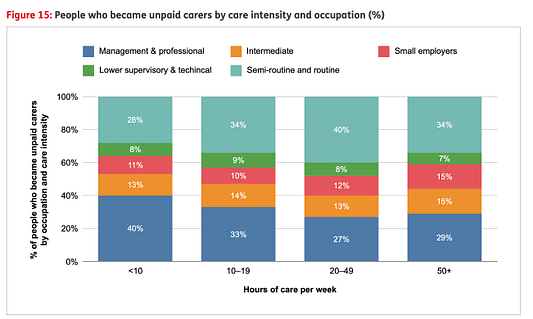

If we look at the list of those struggling with moderate to serious symptoms, many people will appear in multiple groups. For example, Petrillo and Bennett (p.19) found that the two largest groups of unpaid care providers, year on year, were those who held/had held professional/managerial positions, and those who worked/were working semi/routine jobs.

While 34% of carers provided care for 50+ hours a week, the professional and the semi/routine groups delivered most of this care (63%). Just think about all those people providing many hours of care for which they are probably inexperienced, unqualified, and unprepared.

Add to that that while most of the carers are unemployed (60%), over 50 (60%), and unable to obtain full-time work because of the care they are providing, it is not surprising that carers are often struggling with depression in lower-income households, and struggling to make ends meet. And don’t forget, if 60% are not working, 40% are still trying to hold down some form of job and provide care.

To make matters worse, Petrillo and Bennet suggest that 12,000 more unpaid carers are added to the list.

A desire to be appreciated

Whenever I deal with carers, especially daughters who are looking after their mothers, after stripping away the lack of physical, financial and emotional support, one thing that they want is to be appreciated. For someone to say ‘thank you’. They also realise that in many situations, this is a phrase they will never hear from their mother, either because they never have or because the mother has become childlike in their ‘selfishness’: not by choice but by declining capabilities.

Don’t clap for carers; put your arm around them and give them practical and emotional support. Hopefully, this post has highlighted that simple fact – and that our system for caring in the UK has been completely trashed.

Equally importantly, depression is multifaceted. It is not something that can be subjected to a quick fix.